The little boat sailed across the open water almost silently, having no idea of what could be waiting below.

In 1944, 18-year-old Mary Greenwood made the 70-killometer trip across the open waters of the Bay of Fundy in what she calls “lifeboat situations.” During the two-and-a-half hour trip she had no idea that German U-boats were likely slumbering beneath her.

“When I went to take my course we went from St. John, NB, to Digby, NS, in lifeboat situations with our life packs, sailing all the way across,” Mary said. “We were 18, we didn’t know why we were doing this, nobody told us. This is it, we’re doing it.”

Mary was born in August 1926 in Toronto, Ontario. Her grandfather and both of her brothers served in the Navy, so when she came of age, with WWII going on, there was no other logical choice.

Mary was born in August 1926 in Toronto, Ontario. Her grandfather and both of her brothers served in the Navy, so when she came of age, with WWII going on, there was no other logical choice.

“Well the war was on, I was very patriotic, and I am from a Navy family,” Mary said. “There was no way I’d do anything else.”

Mary signed up for the war in the fall of 1944, and was quickly drafted as a sick berth attendant, the equivalent of a civilian nursing assistant. During her training, she worked in Halifax, NS, where most of her patients came in because their feet were in terrible shape from working in submarines.

At the time, girls weren’t allowed on the ships, and because she was only 18, Mary never went overseas. Instead she worked in a hospital in Victoria, British Columbia, for most of the war where she often had as many as 12 patients to look after, with only one nurse on the floor for her to report to.

“We were very busy and we had a lot of responsibility,” she said. “We thought the nurses were gods. Whatever they said was right.”

The hardest patient Mary looked after during the war came wrapped in an oxygen tent. The tent came over the whole bed, giving him a personal no-smoking zone. He’d developed an infection in his lungs, slightly more severe than pneumonia.

“He was quite sick, he was the sickest person we had,” she said. “I was real nervous or him, like you know, keep alive ― and he wasn’t anywhere near dead, but to my 18-year-old mind it was a big responsibility.”

The soldier did survive, and was eventually sent back home.

Mary stayed in Victoria for half a year after the end of the war, waiting for those who had joined the service before her to get home first. She enjoyed her time there, and has fond memories of her stay.

“I can remember, because we did the same thing in Toronto for training, going out to the park to get a hotdog or hamburger or something to eat in my pyjamas with my overcoat on. I did the same thing in Toronto Western, we went up on the roof to watch the fireworks at exhibition time and stuff like that. There were little things we did that were a little off, but we got away with it.”

After the war she stayed on in the reserves, and finished her schooling at Toronto Western Hospital as a nurse.

“I always wanted to be a nurse. In my day you were either a nurse or a secretary. Those were the two fields that you were given. My mother wanted me to be a nurse, and I trained at a good hospital.”

She said that her work in civilian and navy hospitals were similar, except that in the navy hospitals her patients were generally between the ages of 18 and 25. After the war, most of her patients were Japanese prisoners of war. They were transferred to her from another hospital, and so were usually in good condition by the time she looked them over.

“I was treated very well,” she said. “In those days they treated nurses and ministers with respect.”

After she had completed her RNs, Mary worked in the Navy for another four years ― two in Halifax, NS, and two in Cornwallis, NS.

“Of course in Cornwallis, it was a training centre, so 90 per cent of people were 18 year olds,” Mary said. “They got a little rowdy… I was a little shy when I was a young lady, but when they got a little rowdy I’d go down and say ‘these aren’t nutty bars on my shoulder!’ because you had your stripes up on your shoulder, and they’d go ‘OH!’”

As a reserve nurse, she had to work two weeks in the summer and one evening a week at a military Naval Base in Hamilton on top of her civilian job. Still, there were some perks.

Whenever royalty came over from England, an ambulance was required at the airport, meaning that Mary saw her fair share of royalty.

“We saw Princess Anne on two different trips… and when I was on the reserve in Hamilton we got to see the Queen Mother.”

During her time in Hamilton, Mary was invited to dine at a hotel where the Queen Mother was staying. After the meal she was walking around, thinking of socializing with some peers, when the unbelievable happened.

“They laid a carpet right down beside me, a red carpet, and I looked over and there she came, she didn’t stop of course, but you could have touched her! They were exciting times.”

Mary never took a break from service or got married, and she believes it’s part of the reason she was promoted higher than her peers. After spending six months as a sub-lieutenant she became a lieutenant.

One year, during the New Year’s celebrations, Mary noticed that the commander of her base couldn’t stop grinning. When she asked him “what are you smiling about?” he said he’d seen the lists for the new year, and that she was up for a promotion to Commander.

“And my god, New Year’s came and we got the message and I was very happy. I didn’t have to do anything different, except what I was doing, but it was nice,” Mary said. “I’m proud of it, I’m proud of getting in. But I’m no better than anyone else.”

She was the only nursing commander in Canada’s reserve force.

A navy commander is the same rank as a lieutenant-colonel in the army. After eight more years in the navy, and now in her late 50s, Mary decided to leave. She had put in over 22 years of service.

“I left because I thought I’d been in long enough and there were other people coming up in through the service.”

She retired from civilian nursing at the age of 60.

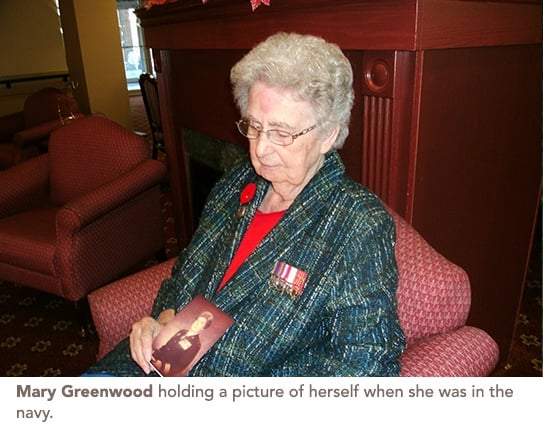

Today, Mary is 90 years old and a resident at Woods Park Care Centre in Barrie, where she lives with her cat. She speaks to her many nieces and nephews fairly frequently, and has one good friend left from her time in the war, who she speaks to every night.

“It’s very nice to talk to her every day,” Mary said. “Every single day we talk.”

CONTACT US 0800 920 2222

.jpg)