Joe Monteyne always knew he wanted to fly. He was born on the family homestead in Saint Rose, Manitoba in July 1921. His family had a quarter section of land and were not considered wealthy. Every year, they participated in the annual animal farm, bringing livestock with them. Every year, there was a pilot who would give people a ride around the fair for five dollars.

Joe Monteyne always knew he wanted to fly. He was born on the family homestead in Saint Rose, Manitoba in July 1921. His family had a quarter section of land and were not considered wealthy. Every year, they participated in the annual animal farm, bringing livestock with them. Every year, there was a pilot who would give people a ride around the fair for five dollars.

“Well, not many people had five dollars for a plane ticket,” Joe said. However, the pilot would stand and speak with him for a few minutes. It was then that Joe became interested in flying.

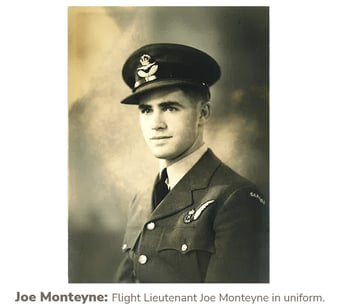

In 1939, war broke out in Europe. In 1942, at the age of 21, Joe joined the Royale Canadian Air Force.

“I knew I didn’t want to be in the army or navy,” Joe said, recounting a story from when he was young. He and four friends had tipped a canoe while crossing a creek, and one boy had almost drowned. “It’s silly when I think about it, as we were flying in a heavy bomber, usually 15-thousand feet over the ocean.”

Joe completed his initial training in Saskatoon. At the end, 15 officers came together to decide his fate in the military.

“They took the control away from you,” Joe said. He’d hoped to be a pilot, but his high marks in math and navigation made him a navigator.

After that, Joe was sent overseas and stationed in Yorkshire, England. It was the most Northern English base and was home to the French-Canadian squadron, which Joe joined. Joe said that while the dangers of the war were always known, it hit much harder once they’d landed in England and were all handed their gas masks.

Joe and his crew flew 35 missions over Nazi-occupied Europe in a single year. Flights were usually 6-7 hours long. Most of them were flown at night, and over the River Valley in Germany.

“We went through a lot of scrapes,” Joe said. Often they’d be in the midst of anti-aircraft fire for an hour before making it to safety. “We went at night and tried to avoid the moon. If we could see them, then they could see us too… It was scary in the sense that if you had any trouble you did not have much time to correct things.”

After their 35th mission, Joe and his crew were grounded and granted leave. They had run the maximum number of allowable missions and were due for a long rest.

Joe was shipped back to Canada in 1945. It took two weeks to return home. During the journey, the war was declared over.

Joe returned home to his family and his girlfriend, Noellie, who was named for being born on Christmas Day. She was a registered nurse and received the Bedside Nursing Medal for her work during the war. They were married in 1947 and had five sons.

Meanwhile, Joe went to work in a lumberyard as a lumberman. Five years later, he was transferred to Northern Alberta where he opened and ran one of the yard’s branches. The branch made a profit in its first year, which was unheard of for the company.

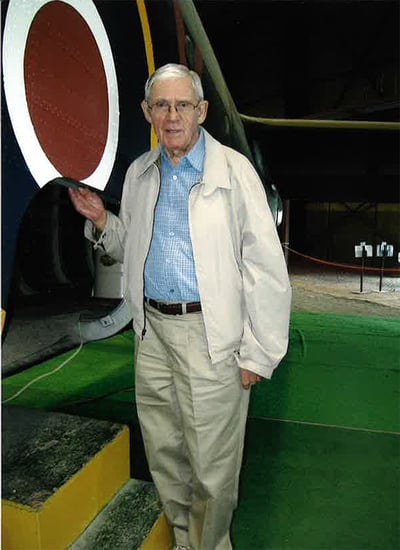

After retiring, Joe spent his time volunteering. He worked with the cadets, as well as doing taxes for people with low income. For 15 years, he did their taxes for free. His favourite part was running into people later in the year and hearing how they were now getting better monetary supplements because of the work he’d done.

Today, Joe continues to enjoy life at Orchard Valley Retirement Residence in Vernon, BC. He is working on his memoirs and recently celebrated his 100th birthday at the residence. When asked about his life, he said:

“I always worked hard, I think that had a lot to do with [living to be 100]. But the war had a big effect on me.”

.jpg)