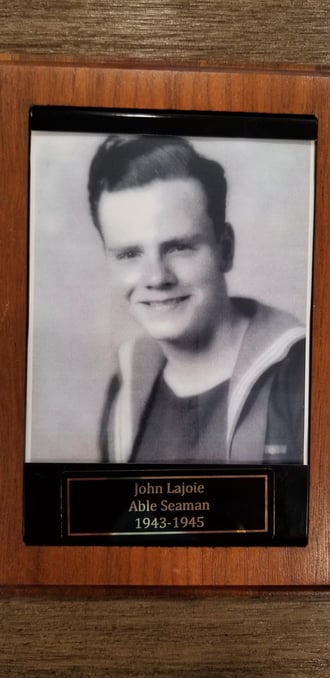

On Remembrance Day, we honour the quiet valor of veterans like John Lajoie, a Kingsmere resident whose wartime narrative differs from the well-trodden battlefields of Europe. His tale is set in the perilous expanse of the North Atlantic, where, as a navy minesweeper during the Second World War, he and his fellow crew members hunted for and deactivated hidden sea mines to ensure the safety of passing vessels.

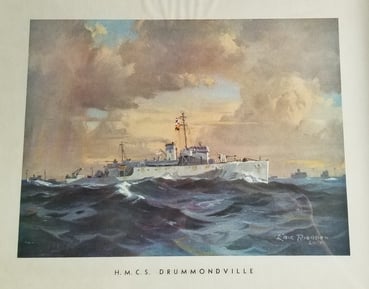

Training and boarding the HMCS Drummondville

Training and boarding the HMCS Drummondville

Enlisting at 17 in 1943, John's military life commenced amidst the turmoil of global strife. His initial training spanned three months at Donnacona — a naval training facility in Montreal — followed by an intensive four-month training program in Cornwallis, Nova Scotia. Subsequently, Lajoie journeyed to Halifax and then onto Newfoundland, where he boarded the HMCS (Her Majesty’s Canadian Ship) Drummondville and joined a minesweeping team that defined his years of service.

Close calls during a dangerous job

The job was fraught with danger. The mines — some planted by allied forces, others by enemies — were a constant worry for those on board when sweeping. "It was tricky at times. Once we would cut the mine cable, the mine would rise to the surface and we had to be careful that we didn’t run into them,” John recalled. “There were a few close calls. They are about the size of a barrel and contain about 600lbs worth of explosives. The ship only has to tap one to blow a hole the size of a truck.” The minesweeper's tools were simple yet vital: a 300-foot cable with clippers to detach mines, lurking just below the surface, from their anchors. Once at the surface they would be destroyed.

Territory covered, convoy work and torpedoed ships

Over three years — two during the war and one after — John's minesweeping duty was spent patrolling up and down the Canadian East Coast with the occasional run down to New York. Sometimes his ship would have to venture as far east as the icy waters of Greenland and Iceland. Sometimes those trips would be for additional minesweeping but the HMCS Drummondville was also involved in “convoy work” as John called it, which was escorting vessels and ensuring their safe passage. It was a dangerous job though and the crew were often on tenterhooks as minesweeping boats were occasionally in the enemy’s crosshairs. "The constant lookout for the enemy was nerve-wracking. We lost two boats from our fleet to torpedoes. We were always on lookout so any sighting of any kind had to be reported,” he recounted. Camaraderie onboard and the end of the war

Camaraderie onboard and the end of the war

Despite the omnipresent risk, the crew's unity was steadfast, sleeping in their swinging hammocks side by side every night. A brotherhood and a self-preserving spirit formed in the cramped confines of their deck. One enduring memory for John was learning of the war's end while at sea. His subsequent conversations with those involved in convoy work in Europe revealed a striking image of German submarines docked in rows at the port of Londonderry in Northern Ireland, their crews already prisoners of war.

Life after the war

Post-conflict life saw John returning to Montreal, where he evolved from a telegraph boy to a dedicated four-decade tenure at Environment Canada. This shift from maritime sentinel to civil servant is a testament to the versatility and fortitude that define many veterans' post-war lives. As we observe Remembrance Day, it's these less heralded yet pivotal stories like John Lajoie’s that form the sturdy underpinning of our collective past. The hazards navigated, the camaraderie cemented, and the moments captured amidst the tumult of the North Atlantic are a tribute to the enduring spirit of those who served. On this day, and every day, we honour the legacy of John and countless others like him.

.jpg)